Myocarditis is a rare cause of cardiovascular disease primarily manifest as sudden death, chest pain or heart failure. The symptoms of heart failure from myocarditis include shortness of breath, fatigue and ankle swelling. The cause is an inflammation of the heart muscle, most often following a viral infection. Between 0.5 and 3.5 percent of heart failure hospitalizations are due to myocarditis. Most cases of myocarditis are identified in young adults with males affected more often than females. The diagnosis should be considered in any young adult with unexplained cardiac causes of shortness of breath or loss of consciousness.

Many authorities recommend the diagnosis be made by heart biopsy, but imaging with magnetic resonance is growing as an accepted diagnostic method. Specific causes of myocarditis vary by world region, which mandates region-specific diagnostic and management strategies. Myocarditis that presents with heart failure symptoms and decreased heart pump function should be treated according to the current national society guidelines for "systolic" heart failure.

Drugs that block the immune system are generally not indicated for the management of the most common forms of myocarditis in adults. However, in specific forms of myocarditis such as giant cell myocarditis, cardiac sarcoidosis or eosinophilic myocarditis, medications that modify the immune response should be considered. These specific forms of myocarditis are diagnosed by heart biopsy.

Sports participation during acute viral myocarditis may cause sudden death. Thus high levels of physical activity following the diagnosis of myocarditis should be avoided for at least 3 to 6 months. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen should be avoided due to a risk of increased inflammation.

Symptoms can include shortness of breath, chest pain, decreased ability to exercise, and an irregular heartbeat. Complications may include heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy or cardiac arrest. For example chest pain and shortness of breath with activity can result from many forms of heart disease and non-cardiac causes. Because the diagnostic tests for cardiac inflammation, magnetic resonance imaging or heart biopsy, are not widely available, the diagnosis is often overlooked. In people who have autoimmune disorders, myocarditis may result from an autoimmune reaction against heart tissues and not a viral infection.

In this setting, myocarditis is a part of a more widespread process that may require treatment with medication to suppress the immune system. Myocarditis can also exacerbate the cardiac damage from other rare heart diseases such as amyloidosis. Many asymptomatic patients with cardiomyopathies aspire to participate in leisure-time and amateur sport activities to take advantage of the multiple benefits of a physically active lifestyle. In 2005, The European Society of Cardiology published recommendations for participation in competitive sport in athletes with cardiomyopathies and myo-pericarditis. One decade on, these recommendations are partly obsolete given the evolving knowledge of the diagnosis, management and treatment of cardiomyopathies and myo-pericarditis.

Myocarditis is clinically and pathologically defined as an inflammation of the heart muscle. The term myocarditis was first used in the early 19th century to describe myocardial diseases not associated with valvular abnormalities , but only in the second half of the 20th century was interest in inflammatory myocardial diseases renewed . A number of patients with acute viral myocarditis may develop dilated cardiomyopathy as a complication (4–19).

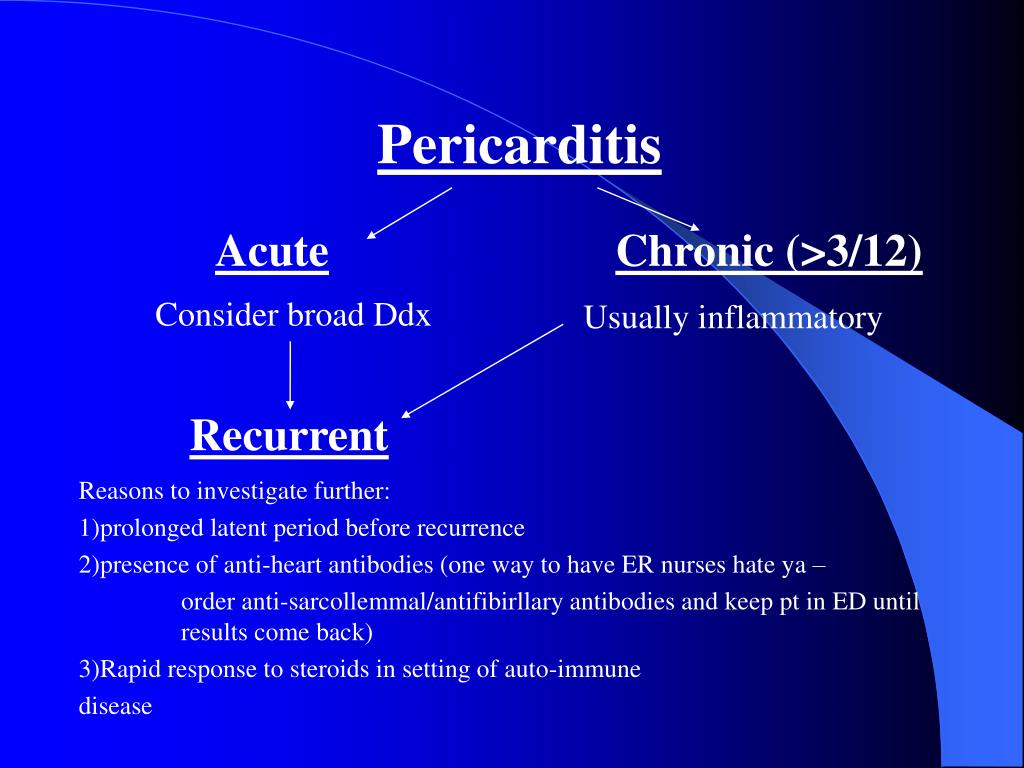

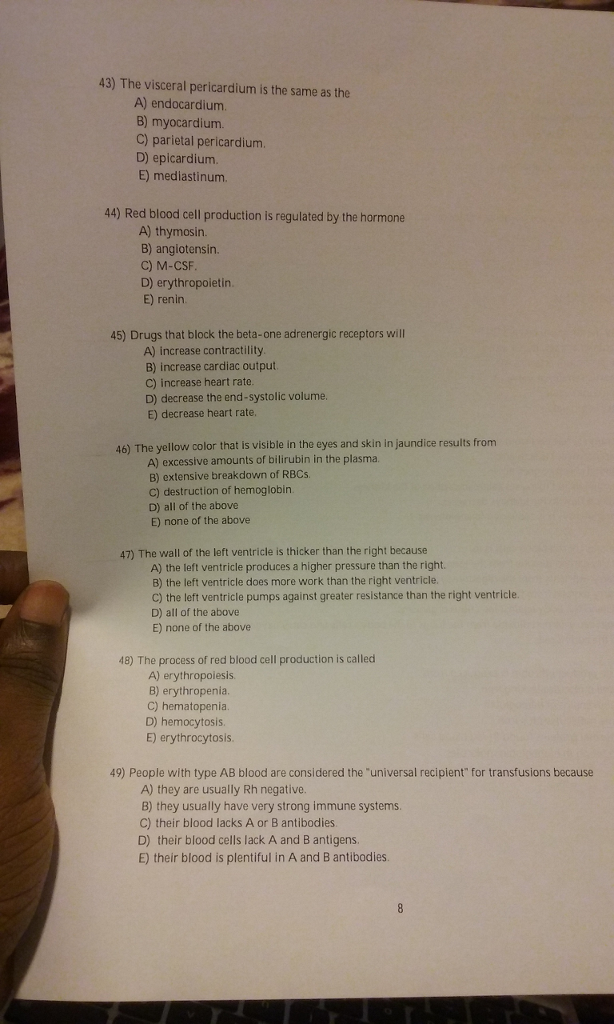

Patients who have suffered from a heart attack may develop pericarditis over the subsequent days or weeks. Pericarditis is a swelling and irritation of the pericardium, the thin sac-like membrane that surrounds the heart. When the symptoms develop more gradually or persist, pericarditis is considered chronic . Myocarditis can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations, from nonspecific symptoms such as fever, myalgia, palpitation and exertional dyspnea to cardiogenic shock or sudden cardiac death .

As in our case, the clinical presentation of myocarditis can be deceptive due to the absence of symptoms, and myocarditis should be considered in cases of systemic infection with concomitant new cardiovascular dysfunctions or elevated cardiac enzymes. Myocarditis also mimics myocardial infarction clinically; therefore, coronary artery disease should be included in the differential diagnosis for myocarditis. Viral infections are known to be the most common cause of myocarditis, and many cases of myocarditis caused by the varicella zoster virus, the human immunodeficiency virus and coxsackievirus have been reported . Tsutsugamushi is primarily localized in the endothelial cells of the heart, lung, brain, kidney, and skin; and within cardiac muscle cells . Tsutsugamushi results in vasculitis in multiple organs, leading to various complications.

Among these complications, cardiac manifestations such as myocarditis, pericarditis and infective endocarditis have been reported . Myocarditis and pericarditis are inflammatory conditions of the heart commonly caused by viral and autoimmune etiologies, although many cases are idiopathic. Emergency clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for these conditions, given the rarity and often nonspecific presentation in the pediatric population. Children with myocarditis may present with a variety of symptoms, ranging from mild flu-like symptoms to overt heart failure and shock, whereas children with pericarditis typically present with chest pain and fever. The cornerstone of therapy for myocarditis includes aggressive supportive management of heart failure, as well as administration of inotropes and antidysrhythmic medications, as indicated.

The acute management of pericarditis includes recognition of tamponade and, if identified, the performance of pericardiocentesis. Medical therapies may include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicine, with steroids reserved for specific populations. This review focuses on the evaluation and treatment of children with myocarditis and/or pericarditis, with an emphasis on currently available medical evidence. Myocarditis should be suspected in people who have recent onset cardiac symptoms, such as chest pains or trouble breathing, and who have no evidence of more common disorders such as coronary artery disease, heart valve damage or severe high blood pressure. In mild cases characteristic features on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging strongly support the diagnosis and heart biopsy is not usually required.

In more severe cases or if patients fail to respond to standard medical care, a heart biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis and guide therapy. There are no specific blood tests to confirm the diagnosis of myocarditis; however, an otherwise unexplained elevation in troponin and/or electrocardiographic features of cardiac injury are supportive. Similarly new heart wall motion abnormalities or a fluid around the heart seen on echocardiography are not specific but support the diagnosis once other more common disorders have been excluded. Myocarditis is clinically and pathologically defined as inflammation of the myocardium. The causes of the inflammation can be numerous and they influence treatment and prognosisFootnote 5. They include infection, medications, cancer treatment and inflammatory diseases.

Age, sex, and genetic and environmental factors can influence disease severity. In children and adolescents, the most frequent cause of myocarditis is viral infection and most have a complete recovery with the right medical management. However, depending on damage to the myocardium, such as myocyte loss and remodelling, myocarditis could have long-term consequences on heart function and increase cardiac susceptibility to other agents and conditions.

The frequency of myocarditis among the general population, including all causes, is estimated at approximately 2 per 100,000 people,Footnote 6 and is predominant in younger male individuals. The clinical course and outcomes vary but are typically longer and can be more severe than what is currently observed in cases associated with COVID-19 vaccines. The symptoms of myocarditis are not specific to the disease and are similar to symptoms of more common heart disorders. A sensation of tightness or squeezing in the chest that is present with rest and with exertion is common. Not infrequently chest pain is improved with leaning forward and worse with lying back when the inflammation affects the outer lining of the heart or pericardium as well as the heart muscle. If the heart pacing or conduction tissues become inflamed, a slow heart rate may cause fatigue or lightheadedness.

Inflammation can also cause extra beats that feel like a flutter in the chest. Sustained runs of extra beats in quick succession may lead to lightheadedness or even loss of consciousness. Sudden death resulting from a myocarditis-related arrhythmia is an important cause of death in children and young athletes. Presentation of acute myocarditis is variable, ranging from subclinical disease to heart failure and patients can present with chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations and fatigue. Most patients respond well to standard treatment, and the prognosis is good. However, it can progress to dilated cardiomyopathy and chronic heart failure, with evidence implicating it in 12% of sudden deaths in adults aged under 40.

Rest is usually recommended in acute pericarditis and acute myocarditis. Given that myocarditis often leads to hospitalization, this task seems easy to carry out in hospital practice; however, it could be a real challenge at home in daily life. Heart rate-lowering treatments (mainly beta-blockers) are usually recommended in case of acute myocarditis, especially in case of heart failure or arrhythmias, but level of proof remains weak.

Calcium channel inhibitors and digoxin are sometimes proposed, albeit in limited situations. It is possible that rest or even heart rate-lowering treatments could help to manage these patients by preventing heart failure as well as by limiting "mechanical inflammation" and controlling arrhythmias, especially life-threatening ones. Several questions remain unsolved, such as the duration of such treatments, especially in light of new heart rate-lowering treatments, such as ivabradine. In this review, we discuss rest and heart-rate lowering medications for the treatment of pericarditis and myocarditis.

We also highlight some work in experimental models that indicates the beneficial effects of such treatments for these conditions. Finally, we suggest certain experimental avenues, through the use of animal models and clinical studies, which could lead to improved management of these patients. A patient presenting to the emergency department with sudden-onset chest pain, ST-segment elevation on his or her ECG, and elevated cardiac biomarkers should alert any clinician to the possibility of acute myocardial infarction . However, acute pericarditis, myocarditis, or myopericarditis are also associated with these findings.

The lack of a true criterion standard for diagnosing pericarditis and myocarditis makes it challenging to differentiate these diseases from AMI.1,2 Early recognition of AMI is crucial for timely initiation of revascularization protocols. Therefore, having a systematic approach to differentiating pericarditis and myocarditis from AMI can help the clinician initiate the appropriate management without delay. The purpose of this article is to review basic features of acute pericarditis and myocarditis and to provide an approach to help clinicians make a timely diagnosis. Heart muscle inflammation is an inflammatory process of the heart muscle, which can be acute or chronic in nature. When both the heart muscle and pericardium are inflamed it is called either Myo-pericarditis or Peri-myocarditis.

In addition to muscle cells, tissue and blood vessels of the heart can also be affected. Heart muscle inflammation is often preceded by a viral infection and is therefore often inconspicuous. The overall health of the person affected and the degree of inflammation are both crucial factors for recovery. Additionally, it is also very difficult to say when exactly the inflammation has resolved.

Myocarditis can affect people of all ages, including those with healthy hearts. Acute pericarditis causes chest pain, which may be very difficult to discern from pain caused by acute myocardial infarction. The chest pain in acute pericarditis may be severe and the patient may also experience cold sweats, tachycardia and anxiety; all of which are common in acute myocardial infarction.

Clinical examination may reveal pericardial friction rub and the echocardiogram may show increased fluid in the pericardial cavity . Hemodynamic compromise may occur if accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac compromises the relaxation and/or contraction of the ventricles and atria. This situation is referred to as cardiac tamponade, which has been discussed earlier. The pericardium is a double-walled sac in which the heart and the roots of the great vessels are contained . The pericardial sac encloses the pericardial cavity which contains pericardial fluid. Numerous conditions may cause inflammation in the pericardium, the pericardial cavity and/or the myocardium.

Pericarditis refers to inflammation of the pericardium, and myocarditis refers to inflammation of the myocardial tissue. However, it is often difficult to differentiate pericarditis and myocarditis, and they tend to accompany each other. Therefore, the term perimyocarditisis often used in clinical practice . The etiology, clinical characteristics and ECG features of pericarditis will be discussed here. From a clinical point of view, clinicians must be able to separate pericarditis from ST elevation myocardial infarction . This may not always be simple, because both conditions bring about severe chest pain and ST elevations on the ECG.

However, as we will discuss below, it is actually rather straightforward to distinguish these two conditions. As a result of these growing reports, several regulatory agencies have added a warning about the risk of myocarditis and pericarditis for COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. It should be noted that a causal relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and heart inflammation has not been established and that the consensus view is that the benefits of vaccination continue to outweigh the risks. Nonetheless, understanding the mechanisms underlying vaccine-associated heart disease is essential for prevention and treatment. The Chief Science Advisor convened a meeting with scientific experts on June 25, 2021, to discuss emerging reports of rare cases of heart inflammation consistent with myocarditis and pericarditis following administration of mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines.

Most cases of myocarditis and pericarditis following COVID-19 vaccination have been reported from Israel and the USA, two countries that are well along in the administration of the second dose of mRNA vaccines. Cases have been predominantly reported in younger males (12-29 year age group mostly) shortly following the second dose of mRNA vaccine . Cases in older adults have also been reported and the outcome has varied depending on other pre-existing conditionsFootnote 2, Footnote 3, Footnote 4.

The Israeli Ministry of Health reported 121 cases out of more than 5 million second doses within 30 days of vaccination. Early data from the Vaccine Safety Datalink in the USA reported 12.6 cases per million second dose of any mRNA vaccine within 21 days of vaccination. In Canada, as of July 9, 163 cases out of 41.5 million total vaccine doses have been reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada, with 67 reported following a first dose. Providers should consider myocarditis and pericarditis in adolescents or young adults with acute chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations. Ask about prior COVID-19 vaccination if you identify these symptoms, as well as relevant other medical, travel, and social history.

To support ongoing surveillance of this potential adverse event, it is imperative that providers report all cases of myocarditis and pericarditis occurring after COVID-19 vaccination to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System . As is the case with pericarditis, viruses are the most common causative agents in myocarditis, but the cause can also be bacterial, fungal, or noninfectious. The clinical presentation of myocarditis can range from minor chest pain to cardiogenic shock. Indeed, myocarditis is associated with more serious long-term sequelae than pericarditis is, the most serious of which are dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Myocarditis and pericarditis are uncommon conditions, usually thought to be related to viral infection leading to inflammation of the heart muscle or the tissue surrounding the heart. Diagnosis is based on elevated levels of cardiac enzymes and specific cardiac tests of electrical activity and structure .

Rates of incidence vary between populations and by gender and age; for example, the incidence in adolescent males aged 14 to 18 years is consistently higher than in females. Estimates of how common these occur depend on how carefully the diagnosis is being looked for.Those recovering from myocarditis are advised to avoid strenuous exercise until fully recovered. Even greater caution should be employed for administering these vaccines to individuals who experienced myocarditis after receiving a first dose. For now, among such individuals second doses should be considered only in those with high risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, or high risk of complications if they develop the disease. Myocarditis, with or without pericarditis, is becoming an increasingly common diagnosis.

Numerous agents are known to cause these heart infections and viruses are considered to be the most important causative agent. Coxsackieviruses B (CV-B) have been involved in 25–40% cases of acute myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy in infants and young adolescents (26–28). CV-B belong to the enterovirus group of the Picornaviridae family and are the causative agents of a broad spectrum of clinically relevant diseases, including acute and chronic myocarditis, meningitis and possibly autoimmune diabetes . The 7.4 kb positive stranded RNA genome of CV-B consists of a 5′-untranslated region followed by a single polyprotein coding region and a 3′-UTR, flanked by a poly A-tail. The first part of the polyprotein encodes the four capsid proteins while the second and third part encode non-structural proteins involved in genome processing and RNA synthesis. The four capsid proteins, VP1-VP4, are grouped into a pseudo-icosahedral capsid.

The VP1–VP3 constitute the outer surface of the viral particle, whilst VP4 is embedded within the inner surface of the capsid . Outbreaks of myocarditis most commonly occur in young children, however sporadic cases are observed in older children and adults (31–34). Clinicians should be aware of the risk of myocarditis and pericarditis with mRNA vaccines and those most likely to be affected. They should be alert to presentations such as acute chest pain, shortness of breath and palpitations that may be suggestive of myocarditis after vaccination, especially in adolescent or young males.